Written by Karel Minor, Humane Pennsylvania President & CEO

Wow. 2024 was one of those years when so much good stuff happened that I had to refer back to my calendar to make sure I remembered everything! We had improvements and expansions of programs, services, and facilities at all our locations and beyond, so let’s dive in. There’s a lot to cover – grab a cup of tea and a comfy chair!

We thought it was great when our communities donated 440,000 pet meals to our pet food donation campaign in 2023. That was so great we took the brazen step of raising our sights – a lot. In 2024 we asked you to help us meet a Million Meal Challenge. You came through. As I type, we are up to 1.47 million meals donated, and counting! That’s nearly triple the previous year!

We thought it was great when our communities donated 440,000 pet meals to our pet food donation campaign in 2023. That was so great we took the brazen step of raising our sights – a lot. In 2024 we asked you to help us meet a Million Meal Challenge. You came through. As I type, we are up to 1.47 million meals donated, and counting! That’s nearly triple the previous year!

Why is this important? HPA has long known, and more recently proven via surveys providing high-level data, that economic and food uncertainty is one of the greatest drivers of pet relinquishment and family stress. Frequently, short-term problems from job loss or some other crisis lead to the permanent decision to give up a pet. Why should a pet or family face this when temporary food support would prevent it? It’s a no-brainer approach – affordable, community-supported, and a long-term impact for a short-term input of help.

That leads to a couple more exciting upgrades to HPA’s Spike’s Pet Food Pantry (SPP) services. First, the main SPP distribution location at the Giorgi Family Community Resource Center (CRC) received a makeover and expansion. SPP services had been limited due to bottlenecks from limited space and limited supplies. With the help of several dedicated volunteers and staff, we converted about 2,000 square feet of the CRC into a full-on “pet supply store” to serve our SPP clients. With shopping carts, a retail-style checkout counter and register, and extended hours, the new space is allowing us to distribute nearly triple the amount of food, with fewer staff and volunteers needed (saving time and money), and avoiding lines and waiting for our clients.

We also know that time and travel are two major hurdles for those struggling financially. So we have begun installing Spike’s Pet Food Pantry Kiosks in our Adoption Centers. These are SPP “light” with a more limited selection but open seven days a week, making access easier.

We also know that time and travel are two major hurdles for those struggling financially. So we have begun installing Spike’s Pet Food Pantry Kiosks in our Adoption Centers. These are SPP “light” with a more limited selection but open seven days a week, making access easier.

We also finalized our test run of using SPP “member” cards to streamline and speed up enrollment, tracking, and distribution. Each client receives a personalized bar-coded member card that can be scanned at checkout for tracking and verification. Watch out Sam’s Club, we’re coming for you! Clients are enrolled for one year based on financial need and have access to pet food and supplies. Most items are provided for 25 cents per pound, making them extremely affordable and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the program. Our clients have made it clear that most do not need or want a hand-out, they need a hand up. For those who are unable to pay even this small amount, food is made available at no charge. The cards also give discounts for low-cost veterinary care at our clinics.

Although programs like this are no longer as controversial as they used to be – 16 years ago we got hate mail for distributing food! – we make sure that donor generosity isn’t being abused. Fortunately, the vast majority of people are good, and our data shows that most people only use this program for a short period. Those who need more help get direct, intensive support. The exceptionally small number who are scammers get booted and banned. I’m glad to know that this program is there for any of us who might need it in a pinch.

donor generosity isn’t being abused. Fortunately, the vast majority of people are good, and our data shows that most people only use this program for a short period. Those who need more help get direct, intensive support. The exceptionally small number who are scammers get booted and banned. I’m glad to know that this program is there for any of us who might need it in a pinch.

You might be wondering where we got all that sweet shelving and I’m glad you asked! Thanks to some dumb luck and a great deal of sweat, early last year HPA was able to buy about $100,000 worth of retail display and shelving from a Rite Aid closing auction for $4,000! It took staff and volunteers three days to break it down and transport it to our warehouse, but we now have shelving for many more projects inventoried and in storage at our Lititz warehouse.

Not familiar with that location? It’s new, too! In order to add space needed for all our programs and distribution work, we purchased a warehouse in Lancaster County which gives us the extra space we need to receive and sort large donations arriving by tractor-trailer. It’s one of the ways we have been able to expand capacity without having to add staff or overload existing space.

Not familiar with that location? It’s new, too! In order to add space needed for all our programs and distribution work, we purchased a warehouse in Lancaster County which gives us the extra space we need to receive and sort large donations arriving by tractor-trailer. It’s one of the ways we have been able to expand capacity without having to add staff or overload existing space.

All this extra warehouse and workspace also allowed us to expand our statewide emergency response support. HPA has a support MOU with the Great Pennsylvania Red Cross chapter serving 8.7 million people in 61 counties. HPA’s innovative Pet Emergency Pallets (PEP’s) are now distributed throughout PA for ready and rapid access in the case of emergencies. The pallets have all the care items needed for the emergency sheltering ten cats or ten dogs (or mixed), ensuring there is no delay in waiting for the cavalry to arrive. Why should someone have to give up or hand off their pet to a stranger when they can care for it themselves? The best time to help someone’s pet is now, the best person to care for that pet is the caretaker, and the best solutions are local! Since most emergencies are smaller in scale, these PEP’s are the perfect size to meet the need. If it’s a bigger or longer-term need, they also offer crucial time to allow HPA or other groups to get to the scene to assist further.

These PEP’s have also allowed us to blow past our goal of ensuring the capacity to provide care for 1,000 animals in a large-scale emergency. This goal, which was already reached a few years ago through a combination of HPA’s direct sheltering capacity and partnerships with other organizations, was established as part of the Healthy Pets Initiative grant received from the Giorgi Family Foundation. That grant transformed our work and informed new approaches to animal welfare nationwide. It also continues to inspire HPA to find better – bigger and sometimes smaller – ways to do more, for more people and animals, and more affordably. Thanks again to the Giorgi Family!

I hope that chair is comfy because there’s so much more! In 2024 HPA added a new affordable community service: Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, PA’s first affordable, non-profit pet boarding service! We were hearing from our community that they were getting priced out of swanky boarding facilities, often having a boarding bill that was more expensive than their vacation. Why should someone have to choose between traveling with family or having a pet because of the cost of boarding? With Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, they don’t need to. Pets of all kinds can stay safely with HPA, affordably and comfortably, with all the bells and whistles of a fancy place if you want them, but without the mandates and restrictions now so common. Not all dogs like playgroups, and some pets need special handling and care. We are literally the experts with over 100 years of experience. With online booking and two locations (Reading and Lancaster), we began booking up and are now expanding to meet the growing need!

I hope that chair is comfy because there’s so much more! In 2024 HPA added a new affordable community service: Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, PA’s first affordable, non-profit pet boarding service! We were hearing from our community that they were getting priced out of swanky boarding facilities, often having a boarding bill that was more expensive than their vacation. Why should someone have to choose between traveling with family or having a pet because of the cost of boarding? With Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, they don’t need to. Pets of all kinds can stay safely with HPA, affordably and comfortably, with all the bells and whistles of a fancy place if you want them, but without the mandates and restrictions now so common. Not all dogs like playgroups, and some pets need special handling and care. We are literally the experts with over 100 years of experience. With online booking and two locations (Reading and Lancaster), we began booking up and are now expanding to meet the growing need!

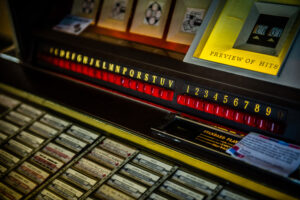

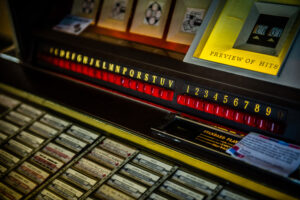

Way back in March, we opened the stunning new Adoption Center for Cats & Critters at our Lancaster campus. It’s awesome. With walk-in group cat rooms, dedicated critter space, a big-a** turtle tank, and even a jukebox full of animal-related rock songs – because who doesn’t want to donate a quarter and listen to “Crocodile Rock”? – it’s really cool. Most of the lighting and fixtures are vintage and donated or found at auctions or Facebook Marketplace. This allowed us to save money, make it way more interesting and eclectic, and reinforce the idea that sometimes the best “new” thing is an older thing. Get it? Like a pet? If you haven’t visited, you should.

As soon as it warms up a little, we will be excited to have the public rededication of the center in honor of two of our very best friends and supporters, Betsy & Ted Lewin. Betsy is a legendary – yep, I’m going with legendary – children’s book illustrator and has been one of the longest-donating artists to our Art for Arf’s Sake Auction. You’ve probably seen her art, and if you have kids you probably have her books in your house right now. I am honored that she is allowing us to recognize her and her late husband, Ted, for their generosity, kindness, and the joy they have given to so many for so long. Stay tuned for the invitation to join us this Spring!

As soon as it warms up a little, we will be excited to have the public rededication of the center in honor of two of our very best friends and supporters, Betsy & Ted Lewin. Betsy is a legendary – yep, I’m going with legendary – children’s book illustrator and has been one of the longest-donating artists to our Art for Arf’s Sake Auction. You’ve probably seen her art, and if you have kids you probably have her books in your house right now. I am honored that she is allowing us to recognize her and her late husband, Ted, for their generosity, kindness, and the joy they have given to so many for so long. Stay tuned for the invitation to join us this Spring!

But wait, there’s more! It took a few months longer than we planned, but The Thrifty Kitty Thrift Boutique opened its doors at the end of the year at our Lancaster Campus! Technically, it may be a reopening since the Humane League used to have a thrift shop. You probably know thrift shops are all the rage. You may not know that although PA’s thrift shops are dominated by Goodwill, religious, and for-profit thrift shops, many parts of the US are dominated by thrift shops benefitting animal shelters.

We spoke to several organizations with thrift shops that were contributing HUGE amounts of money into their charitable work to discover the secret sauce to achieve success. It may come as no surprise but it boils down three big factors we thought we could cover:

the secret sauce to achieve success. It may come as no surprise but it boils down three big factors we thought we could cover:

- Free or super cheap rent (Check! We had an underutilized building on our campus already).

- Sell only donated items (Check! We have so much stuff donated that we could start up fully stocked with great stuff).

- As much volunteer staffing as possible (Check! Mostly – we have volunteers beginning to work in the shop and we have staff volunteering time as we fill the schedule – me included!).

The Thrifty Kitty is open Thursday, Friday, and Saturday from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm, and we’ve got everything and are adding more items until it’s packed to the gills. Stop by and consider volunteering. All volunteers get a discount and shop volunteers get to spot the good stuff as it arrives!

One of the last accomplishments of the past year is also a bit of a heartbreak at the moment. HPA has been quietly providing a unique approach to sterilizing free-roaming cats. Based on our data-driven models and intense intervention approaches of our Healthy Pets Initiative, we broke from the standard model of providing sterilization access. The standard model is to spread the available surgery spots as widely as possible. In the name of being “fair”, everyone was given one or two of the available spots. However, if you have twenty cats in a colony and can only sterilize two per month, all the remaining cats keep breeding and you never get 100% sterilization.

Instead, we offered all available surgical slots to a single colony manager, along with assistance and training for mass trapping, to allow us to get as many in at one time as possible. We also went the extra step of ensuring that any that were missed could be funneled into our regular surgery schedule to get any stragglers. We’d also push in any new cats that wandered in the colony in the future. Once we got them all, we’d move on to the next. Did it work? Boy, did it ever. Between March 2023 and November 2024, about 75 colonies ranging in size from just a couple to dozens of cats were fully sterilized. That’s an accomplishment that has never been achieved in our region before and we subsequently found out that this approach is now being taught in advanced trainings as the way to actually overcome the breeding cycles of free-roaming cats. It turns out we figured it out on our own while others were!

Instead, we offered all available surgical slots to a single colony manager, along with assistance and training for mass trapping, to allow us to get as many in at one time as possible. We also went the extra step of ensuring that any that were missed could be funneled into our regular surgery schedule to get any stragglers. We’d also push in any new cats that wandered in the colony in the future. Once we got them all, we’d move on to the next. Did it work? Boy, did it ever. Between March 2023 and November 2024, about 75 colonies ranging in size from just a couple to dozens of cats were fully sterilized. That’s an accomplishment that has never been achieved in our region before and we subsequently found out that this approach is now being taught in advanced trainings as the way to actually overcome the breeding cycles of free-roaming cats. It turns out we figured it out on our own while others were!

Sadly, this program was paused at the end of the year because the grant that had been funding it was unexpectedly cut. While we are keeping our commitments to ongoing support for sterilized colonies, until we replace the funding this wildly successful program will be shut down. Maybe The Thrifty Kitty can help out with that?

OK, no chair is that comfortable. I’m not even done and this is almost 2,200 words long. That’s the big stuff and we did even so much more than that. Thank you to all the volunteers who helped with any of these accomplishments, as well as to the donors who made it possible and our dedicated staff. We’ve got a lot on the horizon for 2025 and I hope you’ll be a part of it. Please consider volunteering for any of our events or programs. If you can’t volunteer, please consider making a donation in support of the amazing work we are doing for animals and people in Pennsylvania. I didn’t add links in the blog so I could keep you hostage but links to all the mentions are below. Please take a minute to check them out!

Your proud partner in building the best communities anywhere to be an animal of animal caretaker,

Karel Minor, CEO

Humane Pennsylvania

No Pet Hungry: Million Meal Challenge

Spike’s Pet Food Pantry

Emergency Response & Disaster Relief

Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort

Betsy & Ted Lewin Adoption Center for Cats & Critters

The Thrifty Kitty Thrift Boutique

Free Roaming & Community Cat Solutions

Not surprisingly, the greatest risks to pets are found around the home. Plants, foods, human medications, cleaning supplies, and automotive products are responsible for the vast majority of pet poisoning cases reported to veterinarians and poison control centers.

Not surprisingly, the greatest risks to pets are found around the home. Plants, foods, human medications, cleaning supplies, and automotive products are responsible for the vast majority of pet poisoning cases reported to veterinarians and poison control centers. garlic, onions, yeast dough, and any processed foods containing the sweetener Xylitol.

garlic, onions, yeast dough, and any processed foods containing the sweetener Xylitol. In Case of a Pet Poisoning Emergency

In Case of a Pet Poisoning Emergency

While the one-million-pound goal was reached this past year, Humane Pennsylvania is also tackling systemic challenges beyond food with initiatives like low-cost veterinary services and community education.

While the one-million-pound goal was reached this past year, Humane Pennsylvania is also tackling systemic challenges beyond food with initiatives like low-cost veterinary services and community education. After 16 incredible years with Humane Pennsylvania, we are celebrating the retirement of Gloria Hill, Humane Veterinary Hospitals Receptionist. As she prepares for this next chapter, we sat down to reflect on her time with HPA, her favorite memories, and her plans for the future.

After 16 incredible years with Humane Pennsylvania, we are celebrating the retirement of Gloria Hill, Humane Veterinary Hospitals Receptionist. As she prepares for this next chapter, we sat down to reflect on her time with HPA, her favorite memories, and her plans for the future. animals and their caretakers.

animals and their caretakers. What are your plans for retirement? Do you have any fun adventures or hobbies that you are looking forward to?

What are your plans for retirement? Do you have any fun adventures or hobbies that you are looking forward to? We thought it was great when our communities donated 440,000 pet meals to our pet food donation campaign in 2023. That was so great we took the brazen step of raising our sights – a lot. In 2024 we asked you to help us meet a Million Meal Challenge. You came through. As I type, we are up to 1.47 million meals donated, and counting! That’s nearly triple the previous year!

We thought it was great when our communities donated 440,000 pet meals to our pet food donation campaign in 2023. That was so great we took the brazen step of raising our sights – a lot. In 2024 we asked you to help us meet a Million Meal Challenge. You came through. As I type, we are up to 1.47 million meals donated, and counting! That’s nearly triple the previous year!

We also know that time and travel are two major hurdles for those struggling financially. So we have begun installing Spike’s Pet Food Pantry Kiosks in our Adoption Centers. These are SPP “light” with a more limited selection but open seven days a week, making access easier.

We also know that time and travel are two major hurdles for those struggling financially. So we have begun installing Spike’s Pet Food Pantry Kiosks in our Adoption Centers. These are SPP “light” with a more limited selection but open seven days a week, making access easier. donor generosity isn’t being abused. Fortunately, the vast majority of people are good, and our data shows that most people only use this program for a short period. Those who need more help get direct, intensive support. The exceptionally small number who are scammers get booted and banned. I’m glad to know that this program is there for any of us who might need it in a pinch.

donor generosity isn’t being abused. Fortunately, the vast majority of people are good, and our data shows that most people only use this program for a short period. Those who need more help get direct, intensive support. The exceptionally small number who are scammers get booted and banned. I’m glad to know that this program is there for any of us who might need it in a pinch. Not familiar with that location? It’s new, too! In order to add space needed for all our programs and distribution work, we purchased a warehouse in Lancaster County which gives us the extra space we need to receive and sort large donations arriving by tractor-trailer. It’s one of the ways we have been able to expand capacity without having to add staff or overload existing space.

Not familiar with that location? It’s new, too! In order to add space needed for all our programs and distribution work, we purchased a warehouse in Lancaster County which gives us the extra space we need to receive and sort large donations arriving by tractor-trailer. It’s one of the ways we have been able to expand capacity without having to add staff or overload existing space.

I hope that chair is comfy because there’s so much more! In 2024 HPA added a new affordable community service: Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, PA’s first affordable, non-profit pet boarding service! We were hearing from our community that they were getting priced out of swanky boarding facilities, often having a boarding bill that was more expensive than their vacation. Why should someone have to choose between traveling with family or having a pet because of the cost of boarding? With Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, they don’t need to. Pets of all kinds can stay safely with HPA, affordably and comfortably, with all the bells and whistles of a fancy place if you want them, but without the mandates and restrictions now so common. Not all dogs like playgroups, and some pets need special handling and care. We are literally the experts with over 100 years of experience. With online booking and two locations (Reading and Lancaster), we began booking up and are now expanding to meet the growing need!

I hope that chair is comfy because there’s so much more! In 2024 HPA added a new affordable community service: Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, PA’s first affordable, non-profit pet boarding service! We were hearing from our community that they were getting priced out of swanky boarding facilities, often having a boarding bill that was more expensive than their vacation. Why should someone have to choose between traveling with family or having a pet because of the cost of boarding? With Spike & Tilly’s Pet Resort, they don’t need to. Pets of all kinds can stay safely with HPA, affordably and comfortably, with all the bells and whistles of a fancy place if you want them, but without the mandates and restrictions now so common. Not all dogs like playgroups, and some pets need special handling and care. We are literally the experts with over 100 years of experience. With online booking and two locations (Reading and Lancaster), we began booking up and are now expanding to meet the growing need!

As soon as it warms up a little, we will be excited to have the public rededication of the center in honor of two of our very best friends and supporters, Betsy & Ted Lewin. Betsy is a legendary – yep, I’m going with legendary – children’s book illustrator and has been one of the longest-donating artists to our Art for Arf’s Sake Auction. You’ve probably seen her art, and if you have kids you probably have her books in your house right now. I am honored that she is allowing us to recognize her and her late husband, Ted, for their generosity, kindness, and the joy they have given to so many for so long. Stay tuned for the invitation to join us this Spring!

As soon as it warms up a little, we will be excited to have the public rededication of the center in honor of two of our very best friends and supporters, Betsy & Ted Lewin. Betsy is a legendary – yep, I’m going with legendary – children’s book illustrator and has been one of the longest-donating artists to our Art for Arf’s Sake Auction. You’ve probably seen her art, and if you have kids you probably have her books in your house right now. I am honored that she is allowing us to recognize her and her late husband, Ted, for their generosity, kindness, and the joy they have given to so many for so long. Stay tuned for the invitation to join us this Spring! the secret sauce to achieve success. It may come as no surprise but it boils down three big factors we thought we could cover:

the secret sauce to achieve success. It may come as no surprise but it boils down three big factors we thought we could cover: Instead, we offered all available surgical slots to a single colony manager, along with assistance and training for mass trapping, to allow us to get as many in at one time as possible. We also went the extra step of ensuring that any that were missed could be funneled into our regular surgery schedule to get any stragglers. We’d also push in any new cats that wandered in the colony in the future. Once we got them all, we’d move on to the next. Did it work? Boy, did it ever. Between March 2023 and November 2024, about 75 colonies ranging in size from just a couple to dozens of cats were fully sterilized. That’s an accomplishment that has never been achieved in our region before and we subsequently found out that this approach is now being taught in advanced trainings as the way to actually overcome the breeding cycles of free-roaming cats. It turns out we figured it out on our own while others were!

Instead, we offered all available surgical slots to a single colony manager, along with assistance and training for mass trapping, to allow us to get as many in at one time as possible. We also went the extra step of ensuring that any that were missed could be funneled into our regular surgery schedule to get any stragglers. We’d also push in any new cats that wandered in the colony in the future. Once we got them all, we’d move on to the next. Did it work? Boy, did it ever. Between March 2023 and November 2024, about 75 colonies ranging in size from just a couple to dozens of cats were fully sterilized. That’s an accomplishment that has never been achieved in our region before and we subsequently found out that this approach is now being taught in advanced trainings as the way to actually overcome the breeding cycles of free-roaming cats. It turns out we figured it out on our own while others were! A drowning man may be forgiven for not reflecting on the size of the body of water in which he’s drowning. After all, drowning in the ocean, a lake, or a bathtub is still drowning. The volume of the body of water is irrelevant when you’re inhaling it and trying your best to survive.

A drowning man may be forgiven for not reflecting on the size of the body of water in which he’s drowning. After all, drowning in the ocean, a lake, or a bathtub is still drowning. The volume of the body of water is irrelevant when you’re inhaling it and trying your best to survive. Dr. Alicia Simoneau’s 15-year journey with Humane Pennsylvania has been marked by a deep commitment to animal welfare and an unwavering passion for her work. As she celebrates this milestone, it’s clear that Dr. Simoneau’s contributions have been pivotal in shaping the compassionate and dynamic environment that defines Humane Pennsylvania today.

Dr. Alicia Simoneau’s 15-year journey with Humane Pennsylvania has been marked by a deep commitment to animal welfare and an unwavering passion for her work. As she celebrates this milestone, it’s clear that Dr. Simoneau’s contributions have been pivotal in shaping the compassionate and dynamic environment that defines Humane Pennsylvania today.

What’s one thing you’re learning now, and why is it important?

What’s one thing you’re learning now, and why is it important?

Creating a legal will is an opportunity to craft intentional plans that protect your loved ones and eternalize the values that have guided your life, like compassion and caring for animals in need. Legacy support is an easy way to be a part of the solution for years to come.

Creating a legal will is an opportunity to craft intentional plans that protect your loved ones and eternalize the values that have guided your life, like compassion and caring for animals in need. Legacy support is an easy way to be a part of the solution for years to come. After spending over 30 years in the animal welfare world, Humane Pennsylvania (HPA) President & CEO Karel Minor knows a thing or two about helping animals and their caretakers who love them. As the second longest-tenured leader in animal sheltering in Pennsylvania, he is looking back at the progress made and strides taken over his 20 years as CEO of Humane PA.

After spending over 30 years in the animal welfare world, Humane Pennsylvania (HPA) President & CEO Karel Minor knows a thing or two about helping animals and their caretakers who love them. As the second longest-tenured leader in animal sheltering in Pennsylvania, he is looking back at the progress made and strides taken over his 20 years as CEO of Humane PA. be done, usually with no real data to back it up, just opinion and gut feeling. Animal welfare felt hopeless and fatalistic and if you suggested we could save animals’ lives and help people try new things, our peers looked at us like we were stupid. If you suggested adopting cats at Halloween, waiving adoption fees, or adopting at Christmas, people thought you were insane. Twenty years ago, when I started at HPA, which was known as Berks Humane Society at that time, I met a core of staff, board, volunteers, and donors who were willing to be open-minded. They saw that what we had been doing wasn’t working- at least not for the 4,000 animals being euthanized each year- and they took the risk with me to try new and even taboo approaches. It worked, we kept it up, and we helped spread that attitude around the country.

be done, usually with no real data to back it up, just opinion and gut feeling. Animal welfare felt hopeless and fatalistic and if you suggested we could save animals’ lives and help people try new things, our peers looked at us like we were stupid. If you suggested adopting cats at Halloween, waiving adoption fees, or adopting at Christmas, people thought you were insane. Twenty years ago, when I started at HPA, which was known as Berks Humane Society at that time, I met a core of staff, board, volunteers, and donors who were willing to be open-minded. They saw that what we had been doing wasn’t working- at least not for the 4,000 animals being euthanized each year- and they took the risk with me to try new and even taboo approaches. It worked, we kept it up, and we helped spread that attitude around the country. My greatest influence in animal welfare is Dr. Michael Moyer, who hired me at my first shelter 32 years ago. Back then, he was the extremely rare executive director who happened to be a veterinarian. He approached animal welfare like a scientist, used data, and encouraged me to do the same. However, my biggest professional influence is my wife, Dr. Kim Minor, who was one of the extremely rare educators who is a genuine genius, uses data and genuinely cares about doing what’s best for kids, even when it’s hard or personally risky. There is a bizarre similarity to how the education system writes off a lot of kids just like many animal shelters do with animals. Her example of doing what is right for each individual child and how that improves the well-being of children as a population has always motivated me to do the same for animals and the families they are attached to.

My greatest influence in animal welfare is Dr. Michael Moyer, who hired me at my first shelter 32 years ago. Back then, he was the extremely rare executive director who happened to be a veterinarian. He approached animal welfare like a scientist, used data, and encouraged me to do the same. However, my biggest professional influence is my wife, Dr. Kim Minor, who was one of the extremely rare educators who is a genuine genius, uses data and genuinely cares about doing what’s best for kids, even when it’s hard or personally risky. There is a bizarre similarity to how the education system writes off a lot of kids just like many animal shelters do with animals. Her example of doing what is right for each individual child and how that improves the well-being of children as a population has always motivated me to do the same for animals and the families they are attached to. have been with HPA ranging from just one year to nearly twenty years. One person can’t succeed alone and we have built a group who take their work seriously and know they can make a concrete positive difference for the animals and people in our community.

have been with HPA ranging from just one year to nearly twenty years. One person can’t succeed alone and we have built a group who take their work seriously and know they can make a concrete positive difference for the animals and people in our community.

When a mosquito has a blood meal from a dog that has adult heartworms, the microfilaria is taken in by the mosquito and undergoes transformation to a larval stage, which can now be a source of infection for another dog. This larval stage parasite is injected from the mosquito to another dog with the next blood meal the mosquito takes.

When a mosquito has a blood meal from a dog that has adult heartworms, the microfilaria is taken in by the mosquito and undergoes transformation to a larval stage, which can now be a source of infection for another dog. This larval stage parasite is injected from the mosquito to another dog with the next blood meal the mosquito takes. larval stage of the heartworm before it has the chance to mature into an adult worm and cause excessive damage.

larval stage of the heartworm before it has the chance to mature into an adult worm and cause excessive damage.